The Context: Ireland, 1914-18, by Dr William Murphy

Taken together the years 1914 to 1918 constitute the latter stages of the first half of a period of profound instability in Irish politics, a period that stretches from the introduction of the third Home Rule Bill in April 1912 to the end of the Irish Civil War in May 1923. Much of what happened between 1914 and 1918 flowed from the crisis triggered by the attempt to introduce Home Rule, though events in Ireland were also shaped by the dynamics of politics on the island, by policies adopted at Westminster, and by the effects of World War One. At the end of that war Ireland, Britain and the global context had changed. It would not be possible, even if it had been desirable, to return to the pre-war moment when the matter at stake was Home Rule (limited self-government) for Ireland. Indeed, those watching closely during the early months of 1914 may have suspected that Home Rule was already fatally ill. By the closing days of 1918, though there continued to be those in London who viewed it as an unhappy yet still viable basis for a solution to the ‘Irish problem’, for Irish nationalists it was dead. With it had gone the Irish Party, the political movement that had Home Rule as its purpose, and in their stead Sinn Féin ascended, demanding greater levels of autonomy, if possible a republic.

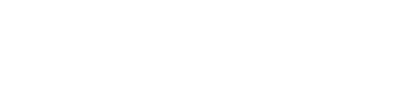

1914 was the year in which Home Rule for the whole of Ireland was supposed to come into effect. The time had arrived, the leadership of the Irish Party imagined, when they became the establishment in a new Ireland. During the early months of the year, however, it became evident that the Liberal government, despite its dependency upon the Irish Party, was unable perhaps, certainly unwilling, to carry through the will of parliament while facing the combined and threatening opposition of Irish unionists and British Conservatives and lacking, as they did, the support of the King and the loyalty of the army. If Home Rule was to proceed it would be on the basis of partition but there seemed little prospect of agreement among the leaders of the Irish Party and unionism as to how much of Ulster should be excluded and for how long. Meanwhile, the paramilitary groups that had emerged to oppose Home Rule (the Ulster Volunteer Force) and to defend Irish self-government (the Irish Volunteers) continued to arm, to drill and to grow.

Then, war in Europe intervened. Six weeks after its outbreak parliament, in an agreed manoeuvre, passed Home Rule and immediately suspended it, averting what had become a serious domestic crisis. It was akin, Prime Minister H.H. Asquith conceded, to ‘cutting off one’s head to get rid of a headache’ yet there was no mistaking the relief. There was a fly in the ointment however. While the establishments – Liberal and Conservative, nationalist and unionist – were prepared to put off the ‘Irish question’, and more than 200,000 Irishmen would enlist to fight Germany, a minority of separatist nationalists were not willing to do either. Imagining themselves in a long tradition of Irish republicans and existing within a contemporary radical milieu that encompassed socialists and suffragists, these separatists were not to be appeased. A minority of this minority – centred on the Irish Republican Brotherhood – was prepared to use the paramilitary forces that had emerged during the preceding years to launch a rebellion. This they did at Easter 1916.

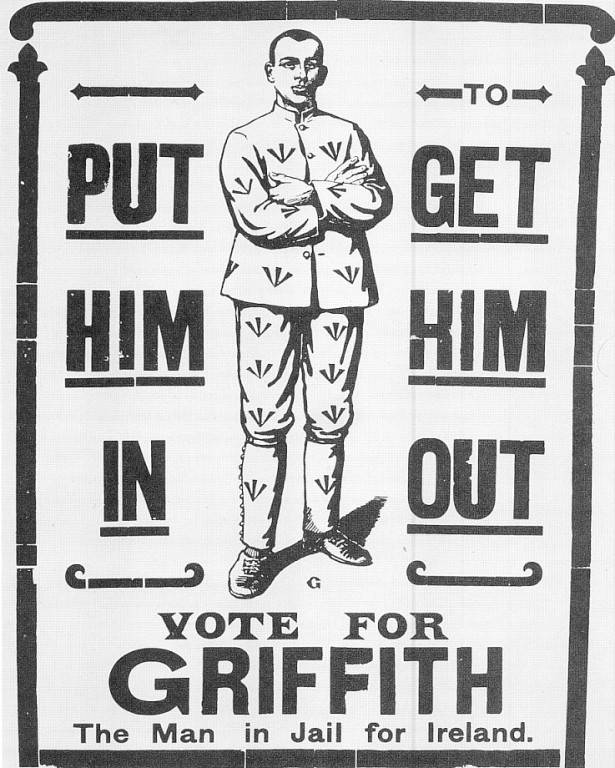

That ‘Rising’ was a military failure but its repression and a subsequent futile attempt to revive Home Rule with partition served both to boost the stock of the radicals and undermine the credibility of the Irish Party with the nationalist public. Growing more confident during 1917 and 1918, the separatists embarked on a strategy of public defiance using the Irish Volunteers: the clampdown on this furthered their cause once more. In parallel, and albeit with considerable mutual suspicion, the various separatist factions coalesced into a political force under the banner of Sinn Féin and set about defeating the Irish Party at the polls. With Arthur Griffith’s victory at the East Cavan by-election in June 1918 Sinn Féin acquired its fifth member of parliament. Count George Noble Plunkett, the father of Joseph Mary Plunkett, one of the executed leaders of the Rising, had been the first elected on a separatist platform as early as February 1917.

All the while the war played into their hands. It ensured that the British government – from May 1915 a wartime coalition – allowed the renewed crisis to build. They not only failed to bolster the Irish Party, they fueled Sinn Féin during 1917 and 1918, radicalizing nationalist public opinion through repression of a vacillating and ineffective variety and by threatening to introduce conscription to Ireland in the spring of 1918. Nearly two million people signed an anti-conscription pledge in Ireland that April, and though the Irish Party and the Catholic Church participated in the campaign it was Sinn Féin and the Irish Volunteers that grew in members.

At the general election of 14 December 1918 – held just a month after the war’s end – the revolution in Irish nationalist politics was confirmed. The Irish Party won just 6 seats whereas Sinn Féin won 73. Michael Laffan has pointed out that in 37 constituencies a Sinn Féin candidate directly opposed one from the Irish Party and they won 35 of these. Their manifesto promised that they would not take their seats at Westminster but seek to establish an Irish Republic by calling an alternative assembly in Ireland and seeking a place at the post-war peace conference. After all, national self-determination, they believed, would be a key principle of the ‘new’ ground-rules of international relations. On the other hand, unionism remained a substantial minority position in Ireland and a majority position in much of Ulster. Unionists had taken 26 seats at the election, an increase of 8. Further and crucially, though the coalition government was returned its composition had altered radically. The Liberal Party’s vote had collapsed, ensuring that it was now a very junior partner to the Conservatives, despite David Lloyd George’s retention of the post of Prime Minister. The British elite, it seemed, was travelling in the opposite direction to Irish nationalist opinion. In these circumstances, and with some Irish Volunteers determined upon using their guns, the crisis escalated.

Dr William Murphy is a lecturer in the School of History and Geography, DCU. He is the author of Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (2014).